November marks Disability Rights Awareness Month in South Africa — a time to reflect not only on progress made in advancing accessibility, but on the deeper work required to achieve true equality. Accessibility opens the door. But inclusion, real, sustained inclusion, means that persons with disabilities are not just welcomed into existing systems; they help design, build, and lead them.

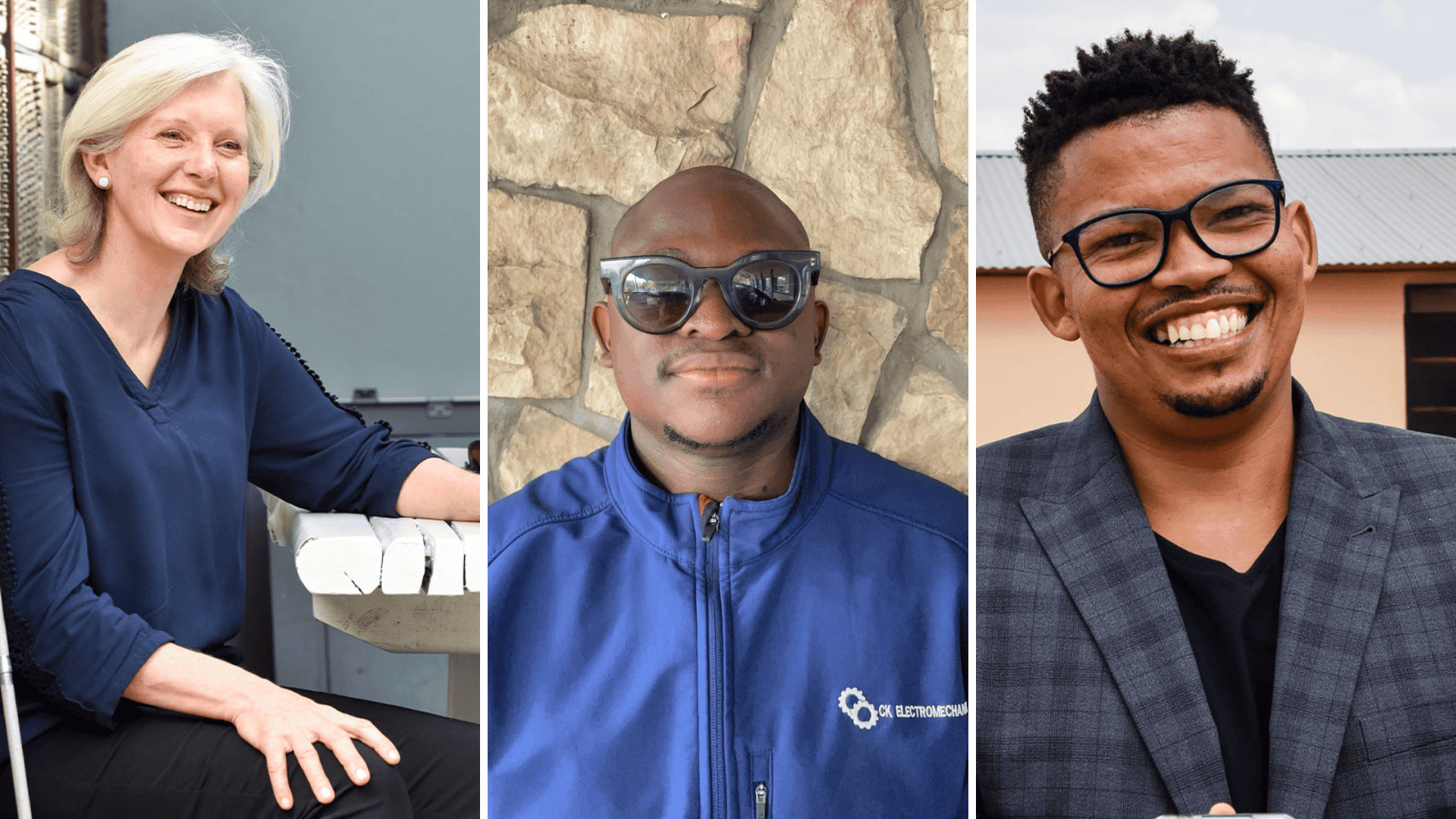

Within the FURTHER community, several entrepreneurs are doing exactly that. They are creating businesses that go beyond serving persons with disabilities to actively employ, train, and empower them as leaders, innovators, and entrepreneurs in their own right.

Two of these changemakers, Sibongile Mongadi, founder of Uku’Hamba, and Ernest Majenge, founder of Ruby Wheelchair (Wheelchair Doctor), are redefining what an inclusive economy looks like, proving that innovation and inclusion can go hand in hand to reshape entire communities.

The story of Uku’Hamba

For Sibongile Mongadi, inclusion is not a slogan, it’s the core of her business philosophy. At Uku’Hamba, she combines technology, social innovation, and environmental sustainability to create affordable, high-quality prosthetics and orthotics for amputees and persons with disabilities.

But her business model is about far more than manufacturing mobility devices. It’s about transforming lives through access to skills and opportunity. “At Uku’Hamba, inclusion drives everything we do,” she explains. “Our business model is designed to empower persons with disabilities not only as users of our products but also as creators, innovators, and leaders within our company and community.”

Uku’Hamba trains and employs persons with disabilities in 3D printing, design, and prosthetic assembly, equipping them with valuable technical skills that lead to financial independence and sustainable livelihoods. This approach transforms the very notion of accessibility — shifting from charity to empowerment, from dependency to leadership.

For Sibongile, an inclusive economy means that everyone, regardless of ability, has equal access to opportunity and dignity. She achieves this by integrating technology, sustainability, and accessibility into every product. By transforming recycled plastic waste into lightweight, affordable prosthetic limbs, Uku’Hamba demonstrates how environmental responsibility and human empowerment can coexist — creating value that is both economic and ethical.

The ripple effects of this model have been remarkable. “Our work has restored confidence, mobility, and independence to individuals who once felt excluded from society,” she says. “We’ve also seen growing awareness and acceptance around disability, shifting mindsets from limitation to empowerment.”

But perhaps most importantly, Sibongile’s work is inspiring a new generation. “By turning waste into opportunity, we’re inspiring youth, especially young women and people with disabilities, to pursue careers in tech and social innovation. At Uku’Hamba, inclusion isn’t just a goal; it’s a movement toward a future where everyone has the chance to move forward.”

The story of Ruby Wheelchair (Wheelchair Doctor)

For Ernest Majenge, inclusion begins with mobility, the foundation of freedom, dignity, and access. Through his company, Ruby Wheelchair (Wheelchair Doctor), Ernest is developing stair-climbing and off-road wheelchairs that enable people with reduced mobility to navigate spaces once deemed inaccessible.

“Our business model is centred around empowerment rather than charity,” he says. “We actively employ and collaborate with persons with disabilities in both the design and assembly stages of our wheelchairs. This ensures that our products are not only functional but also designed with lived experience in mind.”

This approach transforms mobility devices into tools of independence and community development. By providing technical training and small-business opportunities, from repair and maintenance to local sales partnerships, Wheelchair Doctor builds a network of skilled wheelchair technicians with disabilities across South Africa. This not only reduces dependence on external suppliers but creates new pathways for income generation and entrepreneurship within disability communities.

For Ernest, an inclusive economy is one in which persons with disabilities are active participants and decision-makers, not passive recipients. “We are developing mobility solutions that open access to education, workplaces, and public spaces, especially for those in townships and rural areas who are often left behind.”

His approach extends far beyond the product itself. Wheelchair Doctor works with caregivers, schools, hospitals, and rehabilitation centres to build a shared ecosystem of inclusion, one that recognises accessibility as a collective social responsibility.

Ernest’s global partnerships have also played a crucial role. Collaborations with Central State Mobility (USA) and Stella-Rea (Paris), and showcases at GITEX Dubai and the Mandela Washington Fellowship, have allowed him to bring international innovation home, ensuring South Africans have access to world-class mobility solutions developed locally.

The ripple effects are visible. Families who once had to carry loved ones upstairs or across rough terrain now experience freedom and independence. Schools and rehabilitation centres are beginning to adopt new mindsets, seeing mobility as a right, not a privilege. Young innovators in Ekurhuleni and beyond are looking to assistive technology as a viable and exciting career path.

“Our work has inspired others to believe that innovation can emerge from township workshops and change lives globally,” says Ernest.

Sustainability is embedded at every level of the business. The wheelchairs are locally built using durable, repairable materials, extending their lifespan and making them cost-effective. The company also runs awareness and training programmes in collaboration with physiotherapists and rehabilitation centres, ensuring long-term community impact even after products are delivered.

And their work doesn’t stop there. Ernest and his team are advocating for accessibility in public infrastructure, from student accommodation and restaurants to public buildings and Home Affairs offices. “Our goal is to make South Africa, and eventually Africa, a continent where mobility and inclusion are accessible to everyone.”

Building an economy of belonging

As South Africa observes Disability Rights Awareness Month, the stories of Sibongile and Ernest remind us that inclusion must extend beyond ramps, policies, and compliance checklists. It’s about economic participation, who gets to innovate, who gets to earn, and who gets to lead.

Through their work, both entrepreneurs are demonstrating that persons with disabilities are not simply beneficiaries of innovation, they are its architects. By creating businesses that employ, train, and empower persons with disabilities, they’re proving that inclusive economies are not only fairer but stronger. They show us that when accessibility is paired with opportunity, and when inclusion is woven into the fabric of enterprise, we don’t just make the world more accommodating — we make it more human.

At FURTHER, we believe that building an inclusive economy starts with building stronger humans who build stronger communities. And as these entrepreneurs prove, when people are given the tools, the trust, and the chance to lead, they don’t just participate in the economy, they transform it.