The mother tongue of South Africa’s Deaf children

For Deaf children, South African Sign Language is their most natural and first language, but it’s rarely learned from parents or caregivers. Instead, most children are introduced to SASL only at school, where they often learn it from peers rather than adult users.

Unlike spoken languages, which offer Deaf children incomplete visual information, SASL is a visual-gestural language with its own grammar. It is created through the use of hands, facial expressions, directionality, bodily movement, and three-dimensional space, allowing for simultaneously produced information. For Deaf learners, language is built through their eyes.

Why early SASL acquisition matters

A Deaf child who acquires SASL early in life can achieve cognitive, social, and emotional milestones on par with hearing peers. Early exposure to a full, natural language makes it more possible for Deaf children to develop the foundation they need for lifelong learning and emotional well-being.

Can Deaf and hearing children be taught together?

While inclusion is often seen as the ideal, Deaf children can’t thrive in classrooms designed for hearing learners. Every child needs a complete language to learn. SASL can’t be “half taught” through speech supported by signs, nor can it be used simultaneously with spoken English. Deaf learners must be taught in SASL, in classrooms designed for Deaf children, in order to access education fully.

Creating SASL-friendly learning environments

Everything a Deaf child learns and understands comes through their eyes. For this reason, classrooms should be filled with visual learning opportunities, from pictures and age-appropriate labelling to accessible teaching materials. Equally important, all teachers and staff in Deaf schools must have mature literacy in SASL. Since SASL has no written form, schools must also help learners bridge from SASL to written English in order to access broader learning and literacy.

How families can support Deaf children

For hearing parents and families, the first step is recognising that their child’s language is different from their own. Respecting this difference and learning SASL is essential. Families should create a visual learning environment at home and include Deaf children fully in all activities. This builds trust, belonging, and learning opportunities beyond the classroom.

Challenging misconceptions about SASL

Misunderstandings about SASL remain widespread:

- Myth: Sign language is universal.”

Fact: There are over 300 types of sign languages worldwide, each with unique vocabulary and grammar. While SASL shares similarities with other sign languages, it is distinct, with many dialectal variations. - Myth: “SASL is not a real language.”

Fact: SASL is an indigenous, complex natural language with its own structures. It is capable of expressing everything from poetry to philosophy. - Myth: “Learning sign language delays spoken language.”

Fact: The opposite is true. Early exposure to SASL strengthens a Deaf child’s ability to learn written English and helps them face the challenges of spoken languages with greater confidence.

The recognition of SASL as South Africa’s 12th official language

In 2023, SASL was recognised as South Africa’s 12th official language, a historic milestone. Yet in education, little has changed. Policymakers have not fully included Deaf communities, SASL linguists, or SASL-in-education experts in shaping policies that directly affect Deaf learners. Kirsty emphasises the urgent need for collaboration between communities, educators, linguists, and government to ensure that recognition translates into real, systemic change in Deaf education.

Moving forward

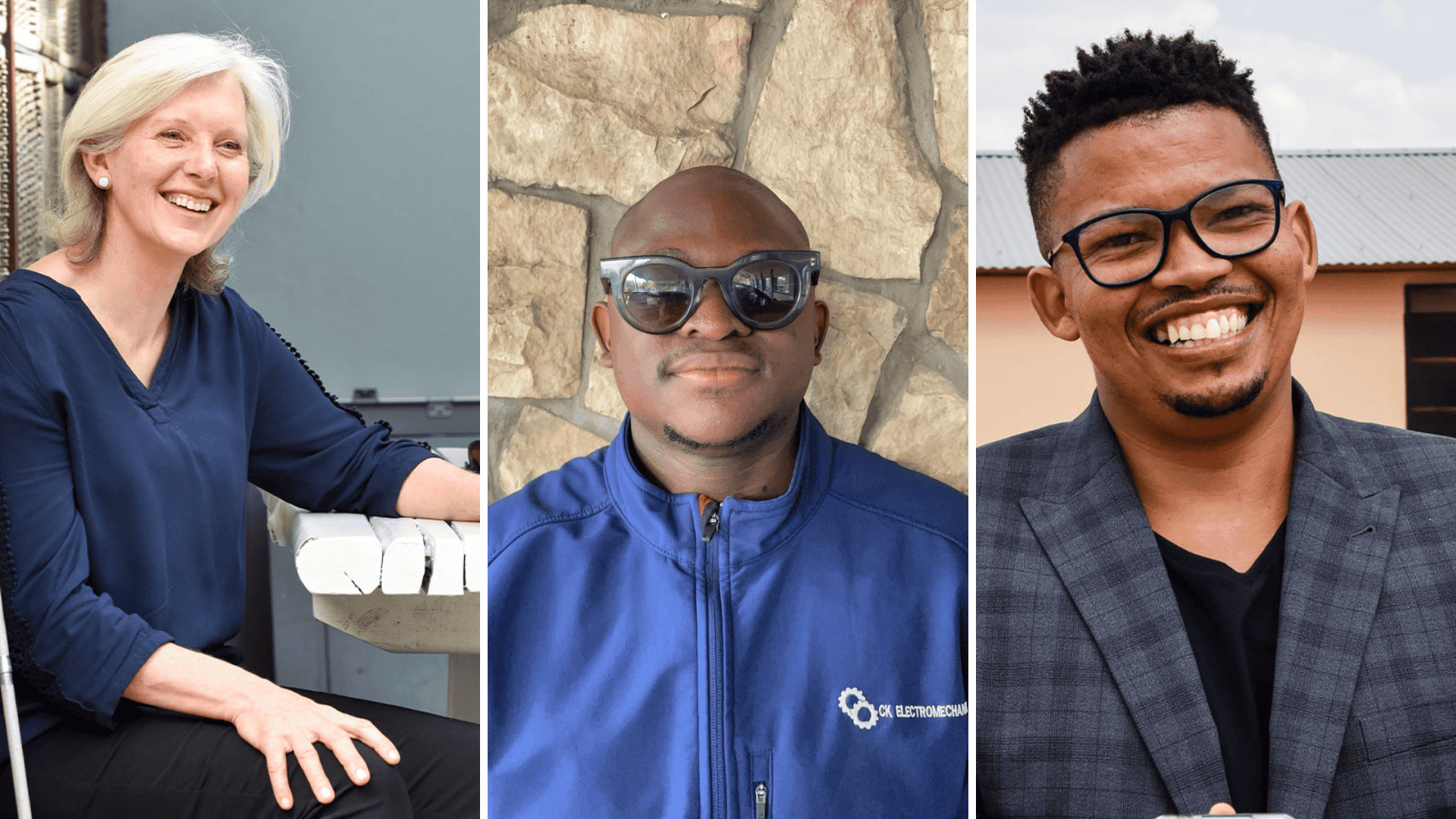

The SLED and SOIL: SLED team are not only giving Deaf children access to literacy and learning but also proving how social innovation can close educational gaps that have persisted for decades.

They continue to champion human capacity development, building the person, not just the skillset, and ensuring that Deaf children in South Africa are seen, heard, and empowered through their own language. Their work is a reminder that when we respect language and culture, we unlock the potential of every child to thrive.